In a academy in a remote corner of the Afghan capital, a din of children’s voices recite Islam’s holiest book.

Sunshine streams through the windows of the Khatamul Anbiya madrassa, where a dozen juvenile boys sit in a circle under the training of their pedagogue, Ismatullah Mudaqiq.

The scholars are awake by 430 AM and start the day with prayers.

They spend class time memorising the Koran, chanting verses until the words are ingrained.

At any moment, Mr Mudaqiq might test them by asking that a verse be recited from memory.

Attention is turning to the future of education in Afghanistan under Taliban rule, with calls among federal educated Afghans and the transnational community for equal access to education for girls and women.

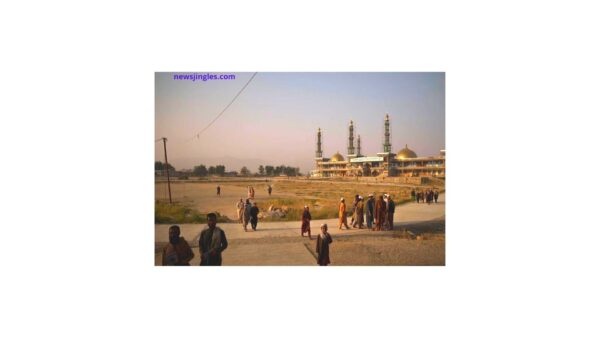

The madrassas — Islamic religious seminaries for meat-and-potatoes and late literacy, attended only by boys — represent another portion of Afghan society, poorer and fresh conservative.

And they too are uncertain what the future will hold under the Taliban.

Paramount of the scholars hail from poor families. For them, madrassas are an important institution; they’re sometimes the only way for their children to get an education, and they’re places where the children are also sheltered, fed and clothed.

At night, the scholars lie on thin mattresses, preferring the ground over rickety bunk beds, until sleep comes.

Like top institutions in Afghanistan, madrassas have plodded during the decline of the country’s scrimping, which has accelerated since the Taliban preemption on August 15.

The Taliban — which means” scholars”— originally cropped in the 1990s, in part from among the scholars of hard- line madrassas in neighbouring Pakistan.

Over the whilom two decades, madrassas in Afghanistan have steered clear of militant testaments, under the eye of the US- backed government fighting the Taliban.

Now that government is gone.

Staff at Khatamul Anbiya were heedful when asked if they hoped for subordinate support from the new Taliban sovereigns.

“Regardless, with or without the Taliban, madrassas are really important,”Mr Mudaqiq said.

“Without them, people will forget their religious sources … The madrassa should always be there no matter what government is present. It does not signify the cost, it should be kept alive.”

Historically, the Afghan government has stipulated the exchequer to furnish education in country areas, enabling madrassas to grow in influence.

The madrassa system has been kept alive largely through community- driven expenditures. Maximum of the aegis comes from private sources.

But with pecuniary detriments due to US permissions and freezes from transnational pecuniary institutions, public pays haven’t been paid. Madrassas aren’t seeing the same fosterage they used to.

The youngish boys who grow up in the madrassa system can qualify to turn religious scholars and experts.

The academies normally instruct a conservative interpretation of Islam and have been criticised for anover-reliance on rote knowledge over critical thinking.